an authentic American perspective*

by Allene Lewis

Branford Marsalis famously opined, “Most people think they know what they like but, actually, they like what they know.” In other words, the more times we hear something, the more familiar and comfortable we become with the track, the more likely we are to like it… or think we like it. Few listeners, therefore, could even conceive of the possibility that a cover of any of their Classic Rock favorites might not only be as good as but even better than the original… and that rule must hold doubly true for a tune as well known and well loved as Layla.

There is very good reason why Eric Clapton does not try to duplicate his original studio arrangement of Layla in his live show. The first half of the song (written by Clapton) included six guitar tracks and seven guitar parts: a rhythm part and three tracks of harmonies played by Clapton, a track of solos by Allman and one track with both Allman and Clapton playing the iconic signature riff doubled in two octaves. The second half (the piano coda written by Jim Gordon and/or Rita Coolidge) features four guitar parts, two (acoustic and slide) by Clapton and two (electric and slide) by Allman.

The slide parts, in particular, are free flowing. Or, put another way, though they have their moments, some of which are magical, they lack a clear, coherent, memorable melody. In addition, there are numerous “creative” passing tones. Or, put another way, in addition to the enchantment, all that free flowing also creates a lot of harmonic conflicts.

Whether you choose to view the coda to Layla as one perfect take (and mix) that could never be duplicated again (either live or in the studio) or merely as another case of us all hearing something so many times that we have gotten use to and can therefore easily overlook all the musical problems and just focus on the vibe, one thing is clear. It’s pointless to try to duplicate that record live or, for that matter, in the studio. It’s never going to come out anything like the original. In fact, even the original was never really “a take” but rather many takes spliced and mixed together by producer Tom Dowd and engineers Howard and Ron Albert. So, in a sense, even the original didn’t come out “just like the record”.

Clapton knows this and doesn’t try to go there. He takes eight pieces, covers about half of the parts on the recorded version, jettisons the slide work (where most of the problems are) and takes a lot of the high notes out of the original melody to make it easier to sing. And audiences love it, right from that first iconic guitar riff, which by the way, was actually written by Duane Allman.

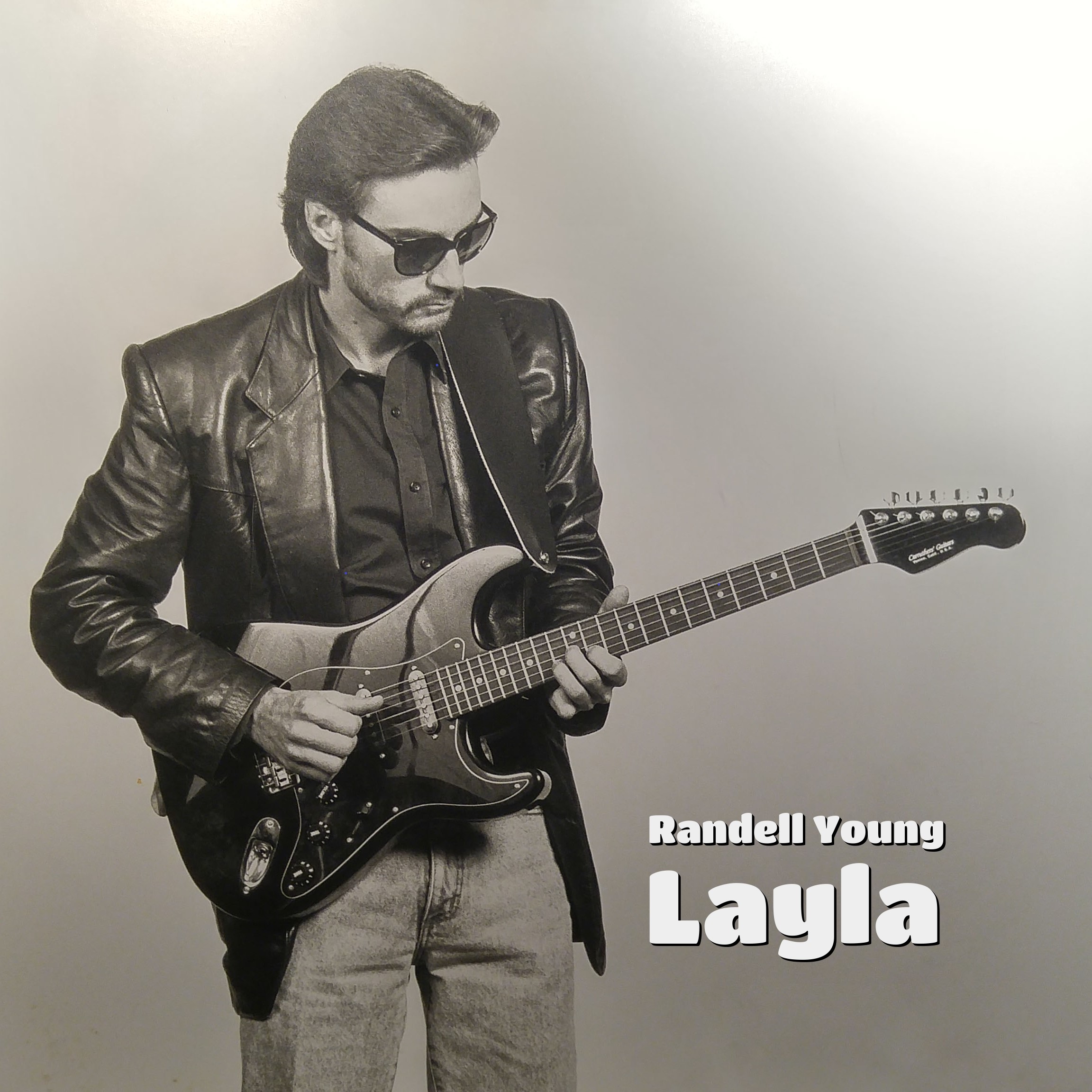

Randell Young’s version of Layla keeps the original key and tempo (and, of course, the iconic guitar riff, repeated all 25 times) but, looking ahead to a live performance, pulls off the entire tune, both the front and back halves, with only four pieces and, aside from the vocals, only eight tracks: one guitar track, one stereo keyboard (enhanced piano) track, one bass track and five drum tracks (kick, snare and hi-hat with left and right overheads capturing the cymbals and toms). There is also a rain stick deployed in the pre-intro but, whether fortuitously or planned, the first bass note lags the guitar, keys and drums just long enough so that live the bassist could play this percussion instrument into his vocal mic.

If you favor a “wall of sound” production concept with so many things happening at once that you could never figure it all out no matter how many times you hear it, this arrangement is not likely to be your cup of tea. If, however, you prefer a Gary Katz/Roger Nichols approach where each instrument and part played is clearly discernible, you may actually prefer this Layla to the original. If so, be careful to whom you voice such sentiments as you are almost certain to be branded a Classic Rock apostate.

Vocally, Young stays meticulously true to the original melody. He didn’t fall in love with his best friend’s wife and then write a song about it. That connection is never going to be there for any performer except Eric Clapton. Nevertheless, Young lays down a strong, confident, soulful and “in character” lead vocal that conveys the frustration contemplated by the lyrics but still takes Layla into a more Rhythm and Blues (as opposed to Hard Rock) direction. Like Young’s lead, the back-up vocals are strictly R&B with all pitches nailed hard, in time and in tune, and no rock singers “almost” hitting the high notes.

The rhythm tracks have been updated with the bass taking a more prominent role in the production while making effective use of all three basic right-hand techniques: thumb slapping, finger popping and traditional finger plucking. That muddy (“what note was that?”) mid-Seventies bass tone is replaced with the aggressive, in-yo-face bass tone of a Marcus Miller or Nate Phillips. The result is a marvelously more modern, rhythmic and even danceable groove.

On the coda, the bass is used to emphasize (and, finally, reprise) Jim Gordon’s classic piano line that comes over the Bb chord and hangs on that dramatic accidental (not in the key of C) Ab before dropping down a half step to resolve back to the fifth of the C chord. It’s Jazzy and clever and one has to figure that Nathan East will want to borrow it as soon as he hears it. Coming out of the coda into the climatic rock show ending, the bass goes back into thumb slapping and string popping mode and thus adds intensity right when it’s needed.

Other than a flamboyant fill announcing the entrance of “the riff”, the drum track never strays from strictly supporting the bass line throughout the whole first half, including the solos, before dropping out entirely just before the beginning of the piano coda. On a decent sound system, you can feel that thump in your chest as the kick drum and bass pulsate perfectly together. Once into the second half, Genovese saves his most ambitious transitional improvisation to set up Young’s final guitar solo. Undoubtedly, these re-envisioned bass and drum tracks (and their expert execution) are what holds this four-piece rendition of Layla together and empowers it to work with only one guitar.

Both tone and performance-wise, the enhanced piano track with percussive attack sounds more 80s than 70s. Like the bass and drum tracks, this helps give this Layla a more jukebox-friendly, dance hall vibe as well as provide Young a more consistent base over which to solo. These are all pretty much standard post-Seventies R&B production devices but ones that you’ve never heard on a Clapton record. If Steely Dan took on Layla, the back-up vocals, keys, bass and drums would, very likely, sound a lot like this.

Like Clapton, Young conjures up his guitar tone using just his amp and instrument, no pedals, no effects other than reverb and a slight tinge of delay. Young’s tone is reminiscent of Clapton but not identical. There is plenty of (actually even more) sustain but, again, taking this Layla into a more R&B direction, he uses slightly less distortion. How does one get more sustain with less distortion? Different pickups? Different strings? Different EQ setting on the amp? Carruthers versus Fender? Is he plucking the strings even more aggressively than Clapton? About the only thing we can rule out is standing closer to the amp as Young is known to always record with his amp in the studio and him playing in the control room.

On the front end of Layla, Young brings a classic, wailing, three-part (beginning, middle and end) guitar solo which incorporates three different variations of a counter melody. Each of the three variations has a mild tension and release phase with the first half pausing on F (the minor third of the underlying Dm chord) and the second half resolving onto the root. Predictably, but satisfying nonetheless, the final variation concludes both halves with a flurry of rhythmically precise 16th notes. It’s a very slick Rhythm and Blues solo that fits the track so well that, even after hearing it only once, you feel like it’s been there all along.

On the coda, Young doubles the piano melody playing a two-note harmony with a clean Smooth Jazz tone, this approach not unlike Clapton’s most recent live version. But on the second pass, Young brings back the over-driven tone to play Jim Gordon’s melody one more time before going into arguably his best guitar work on the tune. Young concludes his Layla with yet another counter melody solo, this one incorporating again that wonderful accidental Ab but this time over the F chord (without dropping the major third) resulting in the most dissonant and dramatic moment of the piece. Then, knowing we want to hear it again (“if they liked it once, they’ll love it twice”) he brings it back, this time an octave higher before burning through a progression of substituted chords with an ending melody that reprises pretty much all the best musical ideas of Layla in one extended finale.

Not many artists have ever tried to cover Layla much less interpret and/or improve it. Young and company set out to create a more modern, rhythmic, R&B version of Layla that could be performed live by just four pieces… provided that three of them are also great singers. And, on those terms, they have succeeded beautifully… and then some.

To put that into perspective, consider these comments by Eric Clapton, “Layla is a difficult song to perform live. It’s [especially] difficult to do as a quartet because there are parts where you have to play and sing completely opposing lines which is almost impossible to do.”

“The Dominos Present: The History of Eric Clapton” describe their live show like this…

“British Rocker Eric Clapton emulated take on American Rhythm and Blues to become the most commercially successful guitarist of all time. Comes now The Dominos, authentic American R&B players with their take on the music of Eric Clapton.”

Can they really give their Layla treatment to all 24 of the Clapton tunes they bring for their live show? That’s a tall order, to be sure, but, whether their “R&B take on Clapton” is a just a marketing come-on or something they can really pull off, they got me. Based on The Dominos’ ambitious and intriguing concept as well as Randell Young’s improbable but clear artistic success with Layla, I am hella Jonesing to see this show.

(*reprinted from Planet Singer with permission)